Let’s see together the relationship between interior and exterior and the ways to interpret it, tell it and live it, and how it has made the history of architecture, and continues to do so. And we will discover the role of cladding as the skin of architecture in the project.

INTERIOR AND EXTERIOR: A FOUNDING COMBINATION IN THE HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURE

Cladding today represents a way to screen the building, to create a filter between the exterior and interior, to design the facades.

In fact it covers a multiplicity of functions and, sometimes, some famous contemporary architecture projects are identified by cladding itself. When we think of these iconic buildings, it is the image of the architectural skin that immediately comes to mind.

However, this way of doing architecture is quite recent, because it is closely linked with current technological possibilities. Once upon a time, although at its dawn, the first concept of decoration and then coating already existed.

We got to see in another content, how Greek and Roman architecture used decorations to give a self-image different from pure matter. And, later, the decoration became a real cladding.

But, nowadays, the cladding is no longer intended as a simple decoration, as an embellishment. It is rather a way to design the relationship between exterior and interior.

This problem was also known to the ancients, who already posed the problem of how to interface between the two dimensions. Homer, in the Odyssey, mentions the mègaron, or the hall of honour at the palace of Ulysses.

One of the first cases in which we find a mègaron of relevance is in the palace of Mycenae, in 1200 BC. It, one of the cardinal rooms of the complex and is positioned following a series of passages and colonnades. These initial rooms, placed in an intermediate position between the entrance and the mègaron itself, act as an architectural filter, in a sort of gradient in the path from outside to inside.

This is a key concept that will be repeated many times in the future. The architects immediately felt the need to cultivate, educate, enrich the physical transition from nature to domestic environments, so that the individual perceived a parallel between the physical path and the spiritual path.

Over time, Greek temples developed these themes in an illustrious way.

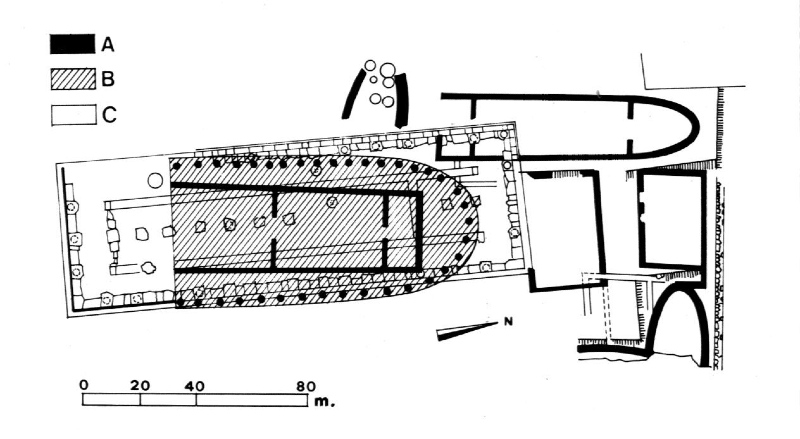

The temple of Apollo in Thermos dates back to 630 BC and has, along its entire perimeter, a colonnade, the so-called pteron, which follows the diaphragmatic function described above.

Plan of the temple of Apollo, Thermos

Source: https://www.pinterest.it/

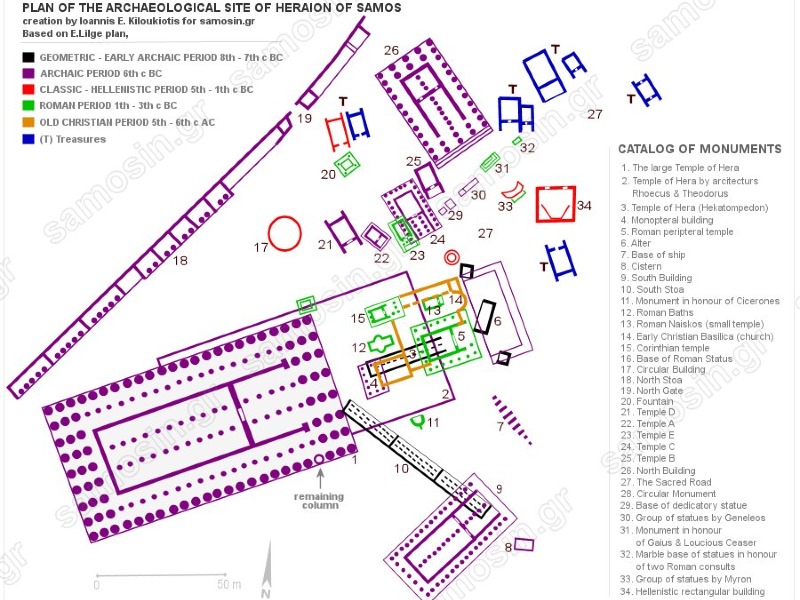

In 550 BC, less than a hundred years later, an unprecedented form of maturity was achieved. In the temple of Hera in Samos there is a double colonnade that emphasises the sense of depth for those who observe from the outside to the inside and ensures that those residing in the heart of the temple have the perception of all that is outside is much farther when in reality it is not.

Plan of the temple of Hera, Samos

Source: https://www.samosin.gr/item/temple-of-hera/

These lessons were also adopted by the Romans, who, masters in the use of the arch, managed to create even wider spans. The Roman baths are, in this sense, examples of architecture in which the dichotomous concept of exterior and interior is almost lost, and upon entering, one has the feeling of never being completely inside and never completely outside architecture until the most central areas are not reached, in an incredible expansion of the spaces. The Romans also left us the first basilicas, from which our Romanesque, Gothic churches and so on derive.

ARCHITECTURAL DIAPHRAGMS, FROM THREE-DIMENSIONAL REALITY TO SKIN: THE ARCHITECTURAL SKIN

On the basis of these prototypes (the basilicas), a new way of separating the outside from the inside was developed in architecture.

The facade is no longer an ongoing play of columns and openings, empty and full. The material surfaces of the masonry and the plaster take over and the glass, which was the preserve of a few, is present in the 16th century in a massive way.

The cladding therefore, increasingly acquires a role in the design of the facade by stripping itself of being a purely decorative garment.

Palazzo Rucellai, in Florence, has one of the most beautiful Renaissance facades in the world. And yet, it is only cladding. The final effect is pursued with the design and use of ad hoc positioned stone slabs. When we think of the building, we think of nothing but its facade, and it will always be studied, probably forever, by analysing its facade.

Rucellai Palace, Florence

Source: https://zloris.blogspot.com/2012/04/leon-battista-alberti-un-genio.html

In the Baroque, the components mix. Borromini’s masterpieces, such as San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, tell us a stylistic register in which the three-dimensional and plastic use of the columns is mixed with the exasperated workmanship of the surfaces.

The architectural skin has its roots in the story told so far, also crossing the volumes and pure surfaces of the Bauhaus, cut cleanly by the typical ribbon windows.

From the use of the diaphragms of columns for the argumentation of the entrances, up to the bare surfaces of Rationalism, passing through the perfectly designed facades of the Renaissance, the concept of architectural skin arose. This today reinterprets the languages and functions of yesterday and always, based on the creative freedom typical of contemporary taste and made possible by current technologies.

THE ARCHITECTURAL SKIN OF THE BUILDING IN THE ARCHITECTURAL SENSITIVITY

One of the first architectures that made use of the concept of leather as we understand it today is Villa Mairea by Alvar Aalto. These drew organic and eclectic masterpieces already in full Rationalism. While colleagues were building machines to live in concrete and glass, Alvar Aalto invented cubes of white plaster matched to natural volumes fully covered with wooden slats.

They simultaneously had multiple purposes: in part, they acted as sunscreens for the grazing northern light, in part they ensured privacy for the inhabitants of the house, in part they simply made the home splendid as we can appreciate today.

Villa Mairea in Alvar Aalto, Noormarkku, Finland

Source: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Villa_Mairea

To date, the use of claddings is now the intellectual property of designers.

The possibilities available to us are vast and the architect is required to have a good design culture and sensitivity so as not to be caught out.

Sometimes the cladding itself is the blueprint.

Superficial, three-dimensional, material, diaphanous, concrete, abstract, spread on the facade or independent to it to form autonomous curves, volumes and edges.

The project for the renovation of Tongji University in Shanghai, by the Archea studio, involves the total covering of the existing brick building, through the use of concrete panels and corrugated and modelled glass fibres ad hoc for the architecture in question. From the outside, the complete renovation of the facades completely renews the architecture and it is the signature protagonist. However, the original forms of the building are kept in mind since the panels, although moved and with an irregular surface, still retain their two-dimensional nature if contextualised to the scale of the building.

The cladding is also the blueprint in many of Gehry’s works. The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao or the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles are a jubilation of sparkling metals, from titanium to aluminium. Although we speak of the practical act of cladding, the term seems to be almost an understatement. In truth, we are no longer able to say that this is the only matter. Rather, from the outside it almost seems to be frontage at full volume.

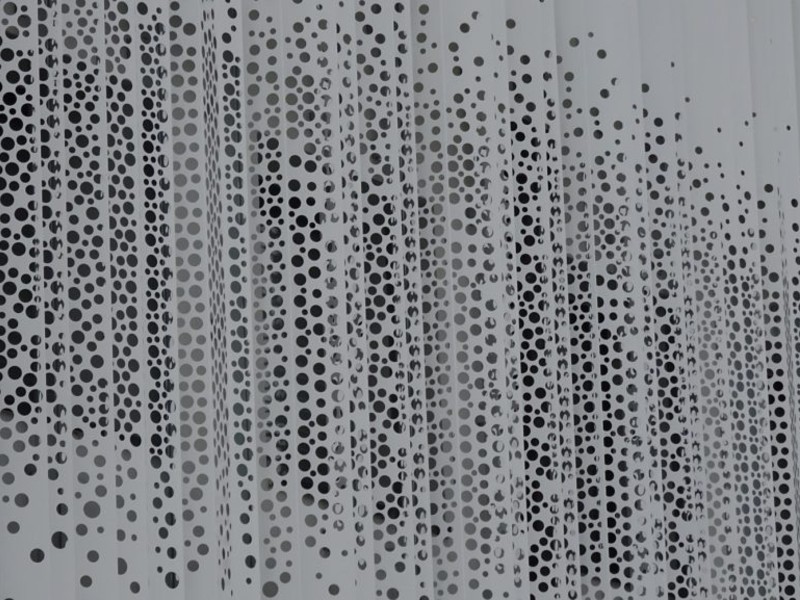

A wonderful example that we cannot forget to mention is Jean Nouvel’s IMA, or the Institute of the Arab World in Paris. This building aims to celebrate Arab culture in France and the integration between the two realities. The facade is articulated by presenting a unique Mashrabiyya pattern that is the old ventilation and lighting systems typical of the Islamic construction tradition.

These are made of glass and aluminum according to a contemporary reinterpretation and are equipped with mobile devices operating as diaphragms and operated by external photocells. They, based on the orientation of the sun, receive solar energy that conditions the opening or closing of the diaphragms, reconfiguring the lighting conditions of the internal environments and the external appearance of the building. The way in which the architectural skin project is a receptacle of so many cultural, identity, functional and aesthetic meanings is admirable.

IMA by Jean Nouvel, Paris

Source: https://www.flickr.com/

Finally, we close with a project by architect Céser Azkarate, who recently built the San Mamés stadium in Bilbao. Also in this case, aluminum is widely used, with the installation of composite panels in Honeycomb. The architectural skin, in this case, is designed according to a game of full and empty spaces that always repeats itself in the attempt, successful at that, to create a unique and continuous pattern for the entire surface of the stadium. The end result is that the observer identifies the stage immediately, associating it with this muscular and plastic image of opaque surfaces and transparencies.

To conclude, therefore, we hope to have highlighted the strength and versatility of the external cladding in today’s architecture. A way to design architecture and its perception from the outside, from the inside and to tell those who experience and enjoy it the relationship between these two worlds.